You can groups rows with the same value into one group or bucket.

group by

If you want to organize your data in groups and calculate some kind of aggregate statistics for these groups, the GROUP BY clause is what you need.

Suppose we’re running a bookstore and want to know how many books of different genres we have in stock. Our database includes a table that lists the books’ titles, genres, and stock quantity.

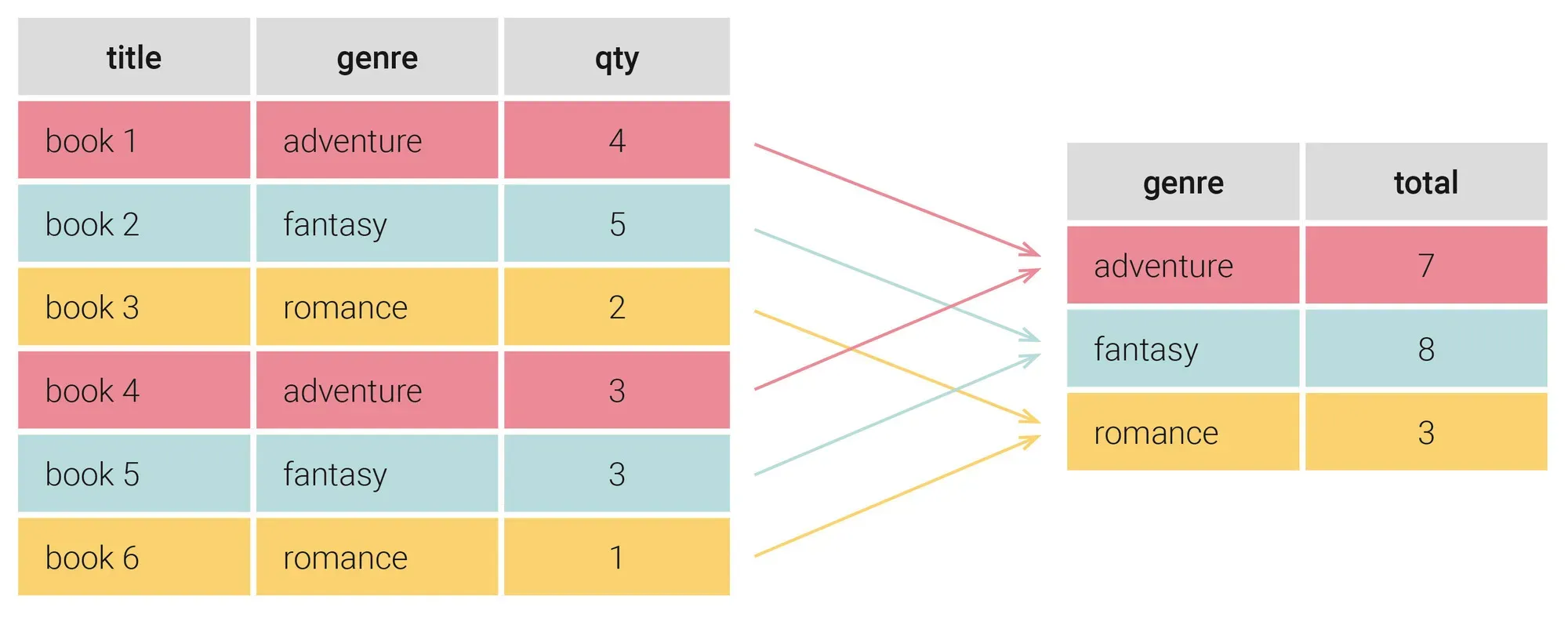

The visualization below shows how the GROUP BY clause creates groups from table data. We want to know the total quantity of books for each genre; thus, GROUP BY groups the books of the same genre and sums up the corresponding quantities. This creates a result table that lists genres and their total quantity of books in our stock.

Now it’s time for more specific examples of SQL queries with a GROUP BY clause.

We’ll use the book table, which stores the id, title, author, genre, language, price, and quantity of each novel we stock.

Example

create table book ( id int unique not null, title text not null, author text not null, genre text not null, lang char(2) not null, price numeric(5,2) not null check (price > 0), qty int not null check (qty >= 0));

insert into book (id, title, author, genre, lang, price, qty) values(1, 'Les Trois Mousquetaires', 'Alexandre Dumas', 'adventure', 'fr', 11.90, 4),(2, 'A Game of Thrones', 'George R.R. Martin', 'fantasy', 'en', 8.49, 5),(3, 'Pride and Prejudice', 'Jane Austen', 'romance', 'en', 9.99, 2),(4, 'Vampire Academy', 'Richelle Mead', 'fantasy', 'en', 7.99, 3),(5, 'Ivanhoe', 'Walter Scott', 'adventure', 'en', 9.99, 3),(6, 'Armance', 'Stendhal', 'romance', 'fr', 5.88, 1);group by is used to bring together those rows in the table that have the same value in all the selected columns.

When you start building a query with group by, you can no longer use select * from table because you are creating a new table with the grouped rows.

And which values will be in the columns that are not grouped?

You can use aggregate functions to compute a single value for each group.

The most common aggregate functions is count which counts the number of rows in each group:

select genre, count(*)from bookgroup by genreHere, in the GROUP BY clause, we select our rows to be grouped by the column genre. Then the count(genre) function in the SELECT statement counts the number of rows within each group (i.e. each book genre), with the result displayed in the corresponding count(*) field:

| genre | count(*) |

|---|---|

| adventure | 2 |

| fantasy | 2 |

| romance | 2 |

Instead of counting the number of rows, you can also use other aggregate functions like sum to calculate the total number of books of each genre:

select genre, sum(qty) as totalfrom bookgroup by genreThe SUM(qty) function in the SELECT statement sums the qty values within each group (i.e. each book genre), with the result displayed in the corresponding total field:

| genre | total |

|---|---|

| adventure | 7 |

| fantasy | 8 |

| romance | 3 |

Using Aggregate Functions with GROUP BY

GROUP BY puts rows with the same value into one bucket. We usually want to compute some statistics for this group of rows, like the average value or the total quantity. To this end, SQL provides aggregate functions that combine values from a certain column into one value for the respective group.

So far, we’ve only used SUM() as our aggregate function for grouping the book titles in stock. However, this is not the only aggregate function you can use with GROUP BY. SQL also offers:

COUNT()to calculate the number of rows in each group.AVG()to find the average value for each group.MIN()to return the minimum value in each group.MAX()to return the maximum value in each group.

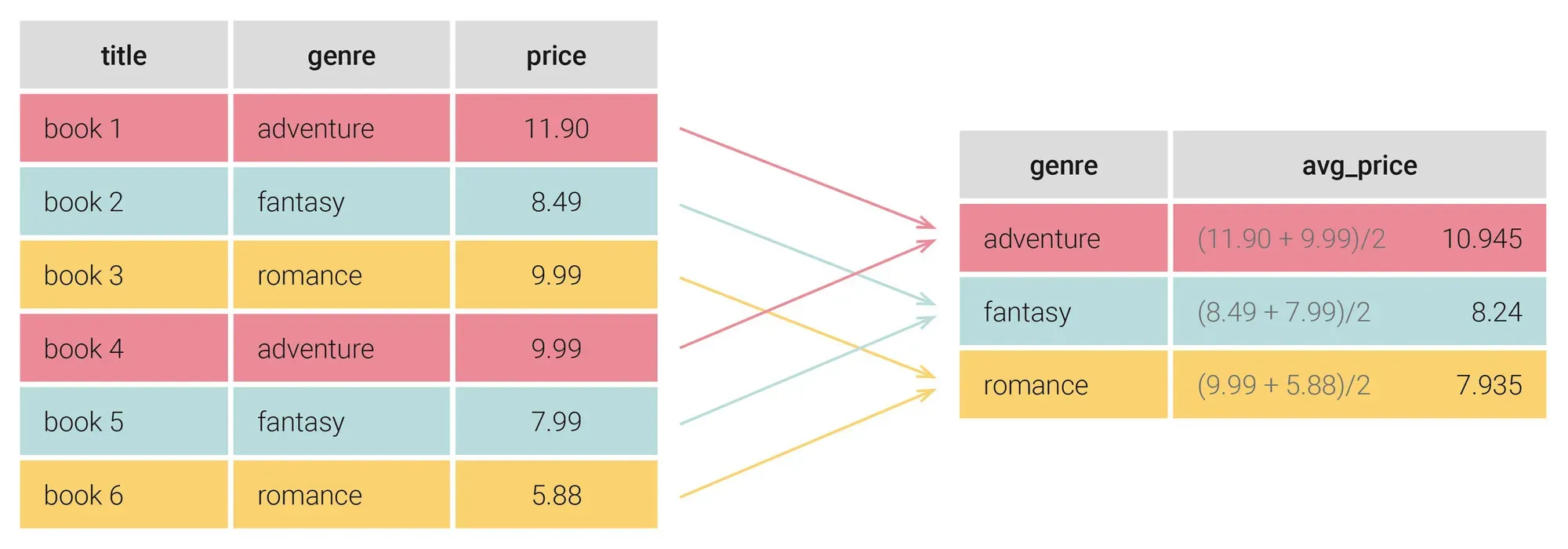

Let’s see how the AVG() function works with GROUP BY. This time, we want to calculate the average price for books in each genre. We’ll start by visualizing the output we want to get.

We’re again grouping our books by genre, but this time we want to calculate the average book price in each genre. The SQL query for this looks as follows:

select genre, avg(price) AS avg_pricefrom bookgroup by genre;This query creates a table with two columns (genre and avg_price), where the average price is calculated by averaging the price values for the books of each genre:

| genre | avg_price |

|---|---|

| adventure | 10.945 |

| fantasy | 8.24 |

| romance | 7.935 |

Actually, we are not limited to using only one aggregate function with a GROUP BY clause.

So, let’s add the information about the minimum and maximum price of the books in each genre:

select genre, min(price) as min_price, avg(price) as avg_price, max(price) as max_pricefrom bookgroup by genre;The result table now contains four columns: genre, min_price, avg_price, and max_price.

| genre | min_price | avg_price | max_price |

|---|---|---|---|

| adventure | 9.99 | 10.945 | 11.9 |

| fantasy | 7.99 | 8.24 | 8.49 |

| romance | 5.88 | 7.935 | 9.99 |

Note that when using GROUP BY the SELECT statement may only include fields that are either used in the aggregate function or listed in the GROUP BY clause.

For example, in our case, we cannot add title or author to our result set. To do so make no sense, as each row in our output table includes information on several books with different titles and authors.

Two columns

In SQL, you can also group your data using several columns. For example, let’s say we want to group our books not only by gender but also by language.

select genre, lang, count(*)from bookgroup by genre, lang;The result table now contains three columns: genre, lang, and count(*). Each row in the table represents the number of books of a certain genre in a certain language.

| genre | lang | titles |

|---|---|---|

| adventure | en | 1 |

| adventure | fr | 1 |

| fantasy | en | 2 |

| romance | en | 1 |

| romance | fr | 1 |

having

The HAVING clause filters groups of rows created by GROUP BY.

It’s similar to WHERE, but instead of filtering individual rows, it filters the aggregated results.

You typically use HAVING when you want conditions on things like:

- total sales per customer

- number of orders per day

- average score per student

In all those cases, the condition refers to an aggregate (SUM, COUNT, AVG, …), so it must go into HAVING, not WHERE.

Basic Example: Sales by Customer

Imagine a sales table:

create table sale ( customer text not null, product text not null, quantity int not null, price numeric(10,2) not null, sale_date date not null);

insert into sale (customer, product, quantity, price, sale_date) values ('david', 'Laptop', 1, 1200.00, '2024-01-05'), ('david', 'Mouse', 2, 25.00, '2024-01-05'), ('susan', 'Monitor', 1, 250.00, '2024-01-06'), ('susan', 'Laptop', 1, 1200.00, '2024-01-10'), ('emma', 'Keyboard', 1, 80.00, '2024-01-15'), ('emma', 'Mouse', 1, 25.00, '2024-01-16');We want all customers whose total spending is at least 500.

First, group by customer and compute total spending:

select customer, sum(quantity * price) as total_spentfrom salegroup by customer;Now add HAVING to keep only customers with total_spent >= 500:

select customer, sum(quantity * price) as total_spentfrom salegroup by customerhaving sum(quantity * price) >= 500;HAVING filters after grouping. It sees one row per customer (with total_spent) and applies the condition there.

With SQLite (and other databases) SELECT aliases are allowed to be used in the GROUP BY clause as well.

So the previous query can also be written as:

select customer, sum(quantity * price) as total_spentfrom salegroup by customerhaving total_spent >= 500;WHERE vs HAVING

WHERE filters rows before grouping.

HAVING filters groups after grouping.

You can use both in one query:

select customer, sum(quantity * price) as total_spentfrom salewhere sale_date >= '2024-01-10'group by customerhaving sum(quantity * price) >= 500;Tasks

create table orders ( id integer unique not null, order_date date not null, status text not null);

insert into orders (id, order_date, status) values (1, '2024-02-01', 'completed'), (2, '2024-02-01', 'completed'), (3, '2024-02-01', 'cancelled'), (4, '2024-02-02', 'completed'), (5, '2024-02-02', 'completed'), (6, '2024-02-02', 'completed'), (7, '2024-02-03', 'pending'), (8, '2024-02-03', 'completed'), (9, '2024-02-03', 'completed'), (10,'2024-02-03', 'completed');Days with More Than 3 Orders

select order_date, count(*) as orders_countfrom ordersgroup by order_datehaving count(*) > 3order by order_date;Days with At Least 3 Completed Orders

select order_date, count(*) as completed_ordersfrom orderswhere status = 'completed'group by order_datehaving count(*) >= 3order by order_date;Task

On April 15, 1912, during her maiden voyage, the widely considered “unsinkable” RMS Titanic sank after colliding with an iceberg. Unfortunately, there weren’t enough lifeboats for everyone on board, resulting in the death of 1502 out of 2224 passengers and crew.

While there was some element of luck involved in surviving, it seems some groups of people were more likely to survive than others.

Import the Titanic dataset from titanic.csv.

Survival count by class

Find how many passengers survived and how many died in each passenger class.

Group by pclass and survived, and count rows in each group.

select pclass, survived, count(*) as passenger_countfrom titanicgroup by pclass, survivedorder by pclass, survived;Average fare by embarkation port

For each embarkation port, calculate the average fare passengers paid.

Group by embarked, use avg(fare).

select embarked, avg(fare) as avg_farefrom titanicgroup by embarkedorder by embarked;Children vs adults by sex

Count how many children, women, and men there were, broken down by sex.

Group by sex and who, count rows in each group.

select sex, who, count(*) as passenger_countfrom titanicgroup by sex, whoorder by sex, who;Average age by survival and class

For each combination of survival status and passenger class, calculate the average age.

Group by survived and pclass, use AVG(age) (it will ignore NULL ages).

select survived, pclass, avg(age) as avg_agefrom titanicgroup by survived, pclassorder by survived, pclass;Classes with at least 50 survivors

For each passenger class, count how many passengers survived. Only show classes where at least 50 passengers survived.

- Filter for

survived = 1(either inWHEREor inside the count condition). - Use

HAVING COUNT(*) >= 50.

select pclass, count(*) as survivorsfrom titanicwhere survived = 1group by pclasshaving count(*) >= 50order by pclass;Ports with high average fare

For each embarkation port, compute the average fare. Show only ports where the average fare is greater than 30.

HAVING AVG(fare) > 30.

select embarked, avg(fare) as avg_farefrom titanicgroup by embarkedhaving avg(fare) > 30order by avg_fare desc;Groups with at least 10 passengers

Group passengers by passenger class and sex. For each group, show: class sex number of passengers Only keep groups that have at least 10 passengers.

GROUP BY pclass, sex and HAVING COUNT(*) >= 10.

select pclass, sex, count(*) as passenger_countfrom titanicgroup by pclass, sexhaving count(*) >= 10order by pclass, sex;Pending

-

Your Year in Data: How SQL Helps You Summarize 12 Months of Information

-

Using GROUP BY in SQL Now that you know SQL’s core commands, power up your queries with the GROUP BY clause and aggregate functions.

-

5 Examples of GROUP BY. When you start learning SQL, you quickly come across the GROUP BY clause. Data grouping—or data aggregation—is an important concept in the world of databases. In this article, we’ll demonstrate how you can use the GROUP BY clause in practice. We’ve gathered five GROUP BY examples, from easier to more complex ones so you can see data grouping in a real-life scenario. As a bonus, you’ll also learn a bit about aggregate functions and the HAVING clause.

-

SQL HAVING Tutorial. Learn how to use the SQL HAVING clause to filter groups using your own specified conditions.

-

What Is the SQL HAVING Clause?. Are you learning SQL? Are you wondering what you can use the HAVING clause for? Or, perhaps, have you tried to use WHERE on your GROUP BY aggregates? You are in the right place! In this article, we explain how to use HAVING with plenty of examples.

-

HAVING vs. WHERE in SQL: What You Should Know. This article is about SQL’s WHERE and HAVING clauses. Both clauses are part of the foundations of the SQL SELECT command. They have similar uses, but there are also important differences that every person who uses SQL should know. Let’s see what’s behind the HAVING vs. WHERE debate.