On this page

Introduction

The central ideas of evolution are that life has a history — it has changed over time — and that different species share common ancestors.

Here, you can explore how evolutionary change and evolutionary relationships are represented in “family trees,” how these trees are constructed, and how this knowledge affects biological classification. You will also find a timeline of evolutionary history and information on some specific events in the history of life: human evolution and the origin of life.

The family tree

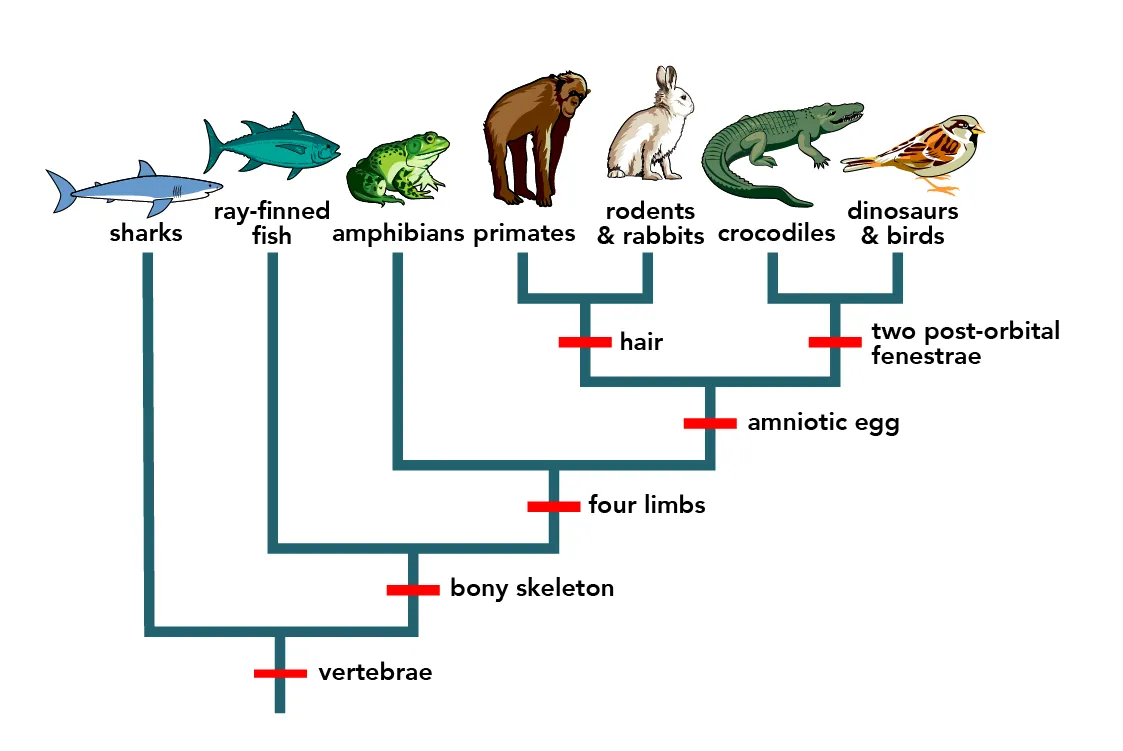

The process of evolution produces a pattern of relationships between species. As lineages evolve and split and modifications are inherited, their evolutionary paths diverge. This produces a branching pattern of evolutionary relationships.

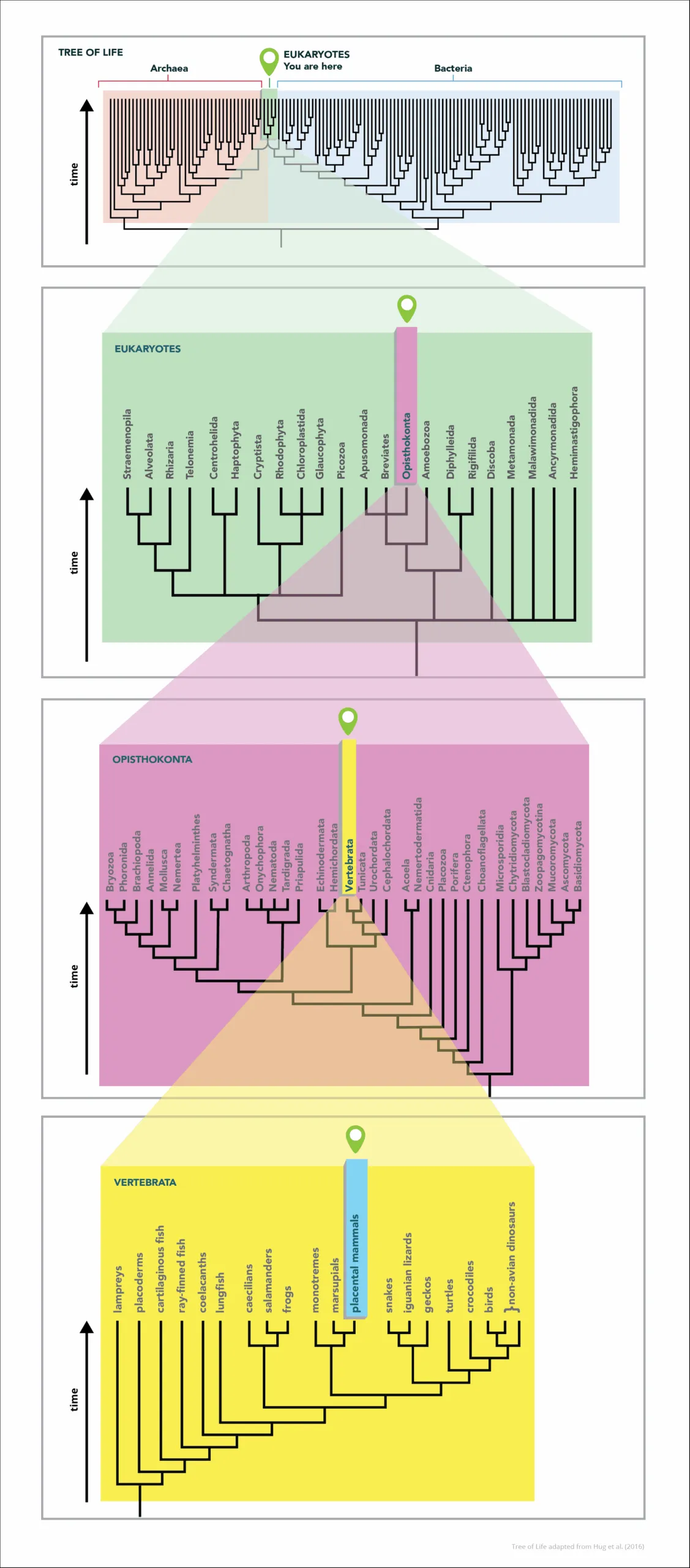

By studying inherited species’ characteristics and other historical evidence, we can reconstruct evolutionary relationships and represent them on a “family tree,” called a phylogeny. The phylogeny you see below represents the basic relationships that tie all life on Earth together.

This tree, like all phylogenetic trees, is a hypothesis about the relationships among organisms. It illustrates the idea that all life is related. As shown below, we can zoom in on particular branches of the tree to explore the phylogeny of particular lineages, for example, the eukaryotes. And then we can zoom in even further to examine some of the major lineages within Eukaryota, for example, the Opisthokonta … and so on.

The tree is supported by many lines of evidence, but it is probably not flawless. Scientists constantly reevaluate hypotheses and compare them to new evidence. As scientists gather even more data, they may revise these particular hypotheses, rearranging some branches on the tree.

For example, evidence discovered in the last 50 years suggests that birds are dinosaurs, which required adjustment to several “vertebrate twigs.”

Understanding phylogenies

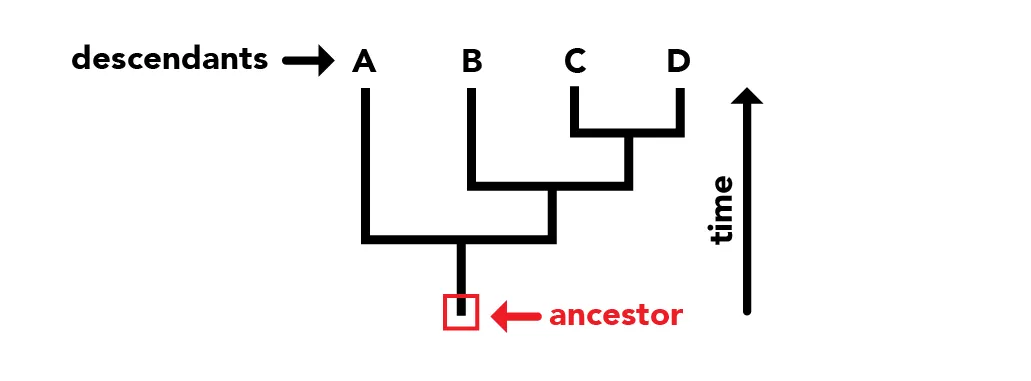

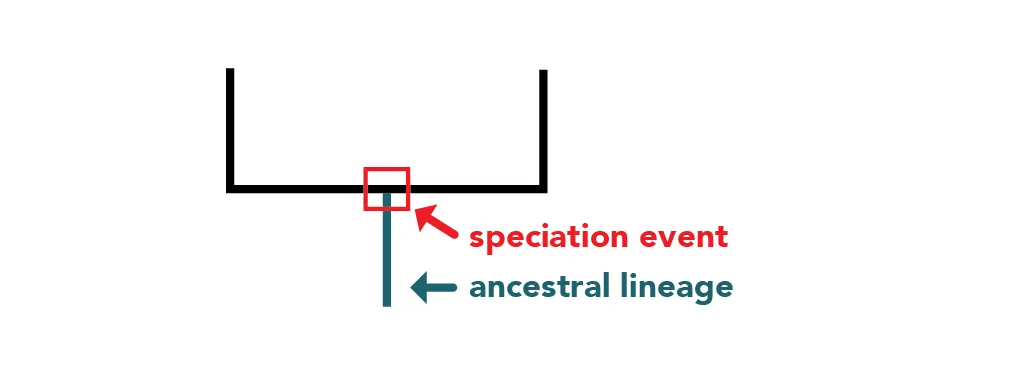

Understanding phylogeny is a lot like reading a family tree. The root of the tree represents the ancestral lineage, and the tips of the branches represent the descendants of that ancestor. As you move from the root to the tips, you are moving forward in time.

When a lineage splits (speciation), it is represented as branching on phylogeny. When a speciation event occurs, a single ancestral lineage gives rise to two or more daughter lineages.

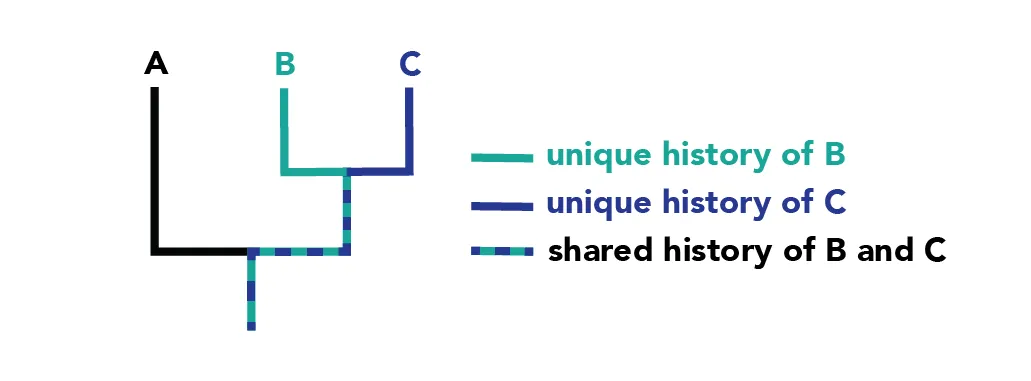

Phylogenies trace patterns of shared ancestry between lineages. Each lineage has a part of its history that is unique to it alone and parts that are shared with other lineages.

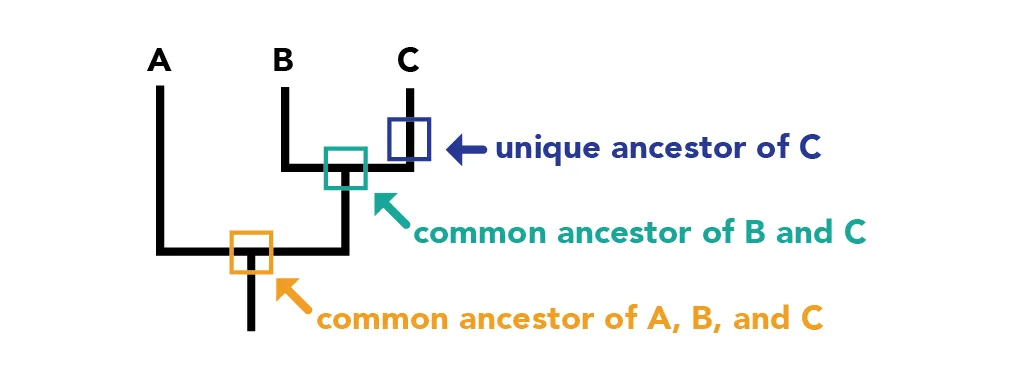

Similarly, each lineage has ancestors that are unique to that lineage and ancestors that are shared with other lineages – common ancestors.

Ancestral organism shared by two or more descendent lineages — in other words, an ancestor that they have in common. For example, the common ancestors of two biological siblings include their parents and grandparents; the common ancestors of a coyote and a wolf include the first canine and the first mammal.

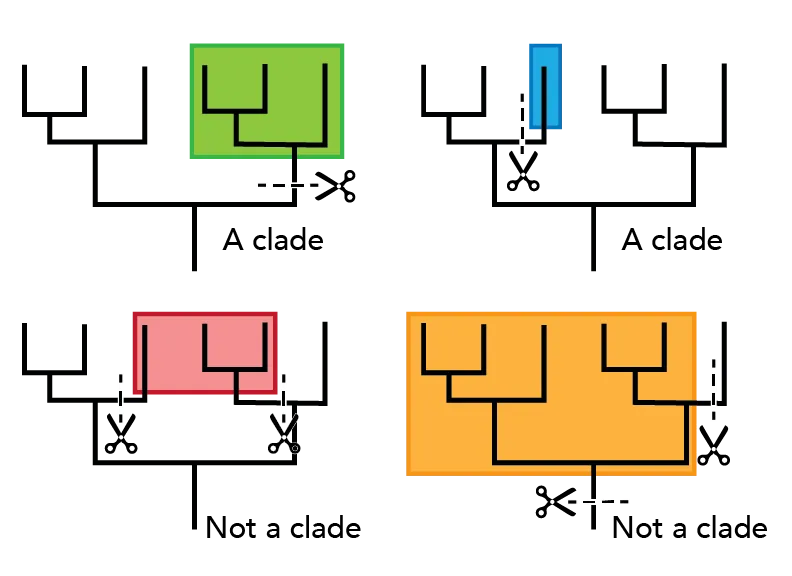

A clade is a grouping that includes a common ancestor and all the descendants (living and extinct) of that ancestor. Using phylogeny, it is easy to tell if a group of lineages forms a clade. Imagine clipping a single branch off the phylogeny — all the organisms on that pruned branch make up a clade.

Clades are nested within one another — they form a nested hierarchy. A clade may include many thousands of species or just a few. Some examples of clades at different levels are marked on the phylogeny below. Notice how clades are nested within larger clades.

So far, we’ve said that the tips of a phylogeny represent descendent lineages. Depending on how many branches of the tree you are including however, the descendants at the tips might be different populations of a species, different species, or different clades, each composed of many species.

Trees, not ladders

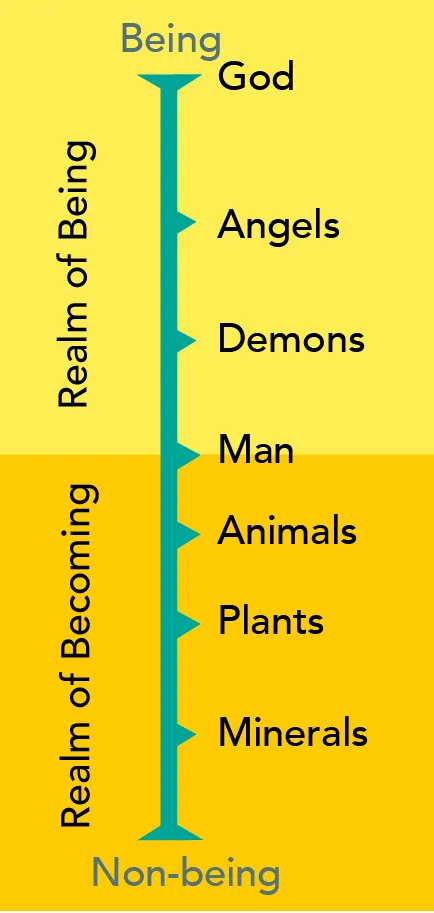

Several times in the past, biologists have committed themselves to the erroneous idea that life can be organized on a ladder of lower to higher organisms.

This idea lies at the heart of Aristotle’s Great Chain of Being:

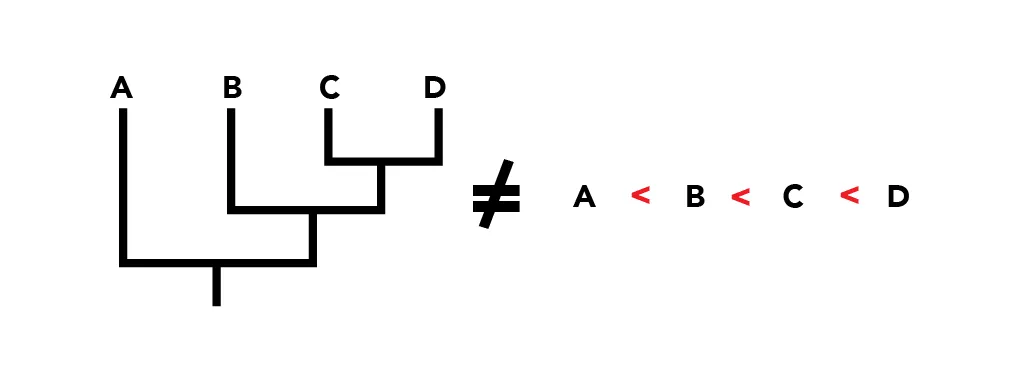

Similarly, it’s easy to misinterpret phylogenies as implying that some organisms are more “advanced” than others; however, phylogenies don’t imply this at all.

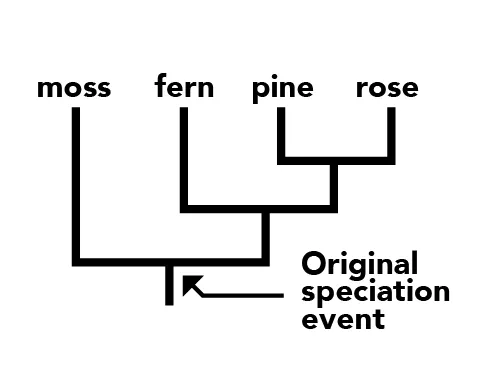

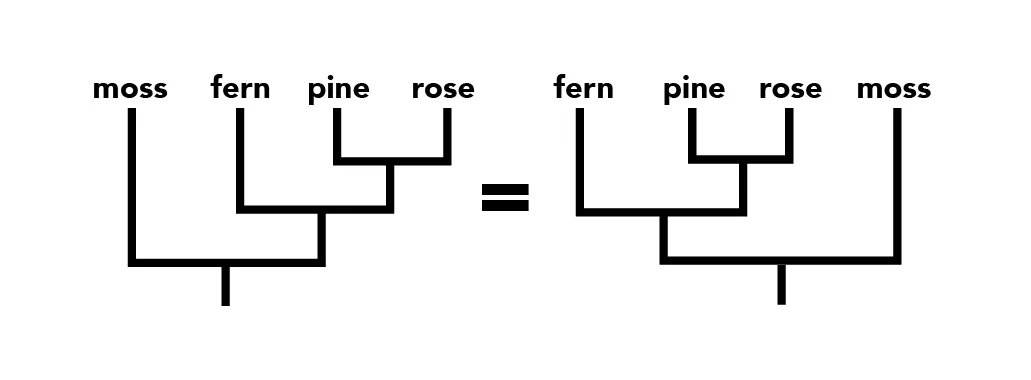

In this highly simplified phylogeny, a speciation event occurred resulting in two lineages. One led to the mosses of today; the other led to the fern, pine, and rose. Since that speciation event, both lineages have had an equal amount of time to evolve. So, although mosses branch off early on the tree of life and share many features with the ancestor of all land plants, living moss species are not ancestral to other land plants. Nor are they more primitive. Mosses are the cousins of other land plants.

So when reading a phylogeny, it is important to keep three things in mind:

-

Evolution produces a pattern of relationships among lineages that is tree-like, not ladder-like.

-

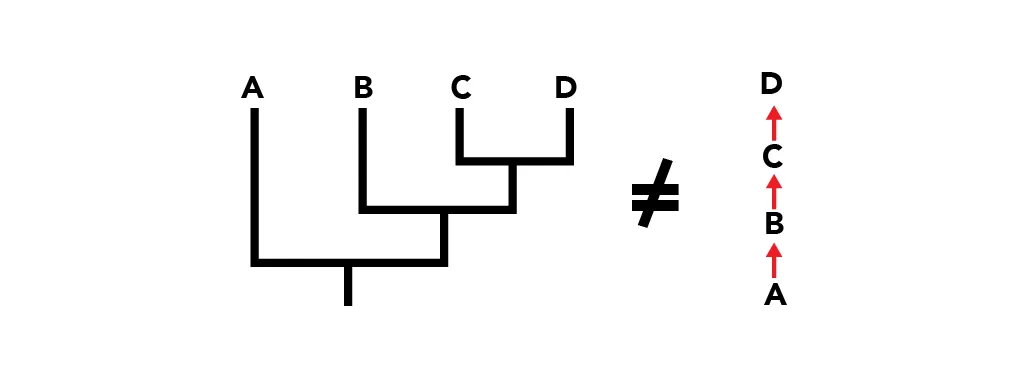

Just because we tend to read phylogenies from left to right, there is no correlation with level of “advancement.”

-

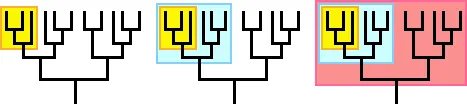

For any speciation event on a phylogeny, the choice of which lineage goes to the right and which goes to the left is arbitrary. The following phylogenies are equivalent:

Biologists often put the clade they are most interested in (whether that is bats, bedbugs, or bacteria) on the right side of the phylogeny.

Misconceptions about humans

The points described above cause the most problems when it comes to human evolution.

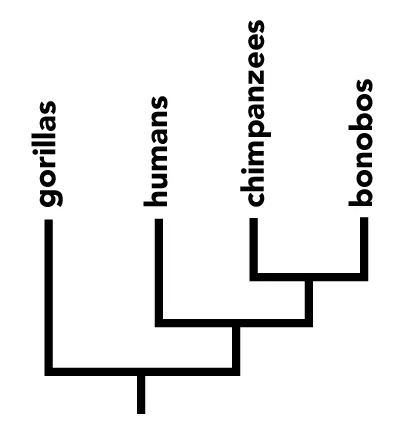

The phylogeny of living species most closely related to us looks like this:

It is important to remember that:

-

Humans did not evolve from chimpanzees. Humans and chimpanzees are evolutionary cousins and share a recent common ancestor that was neither chimpanzee nor human.

-

Humans are not “higher” or “more evolved” than other living lineages. Since our lineages split, humans and chimpanzees have each evolved traits unique to their own lineages.